- Home

- Ioannis Pappos

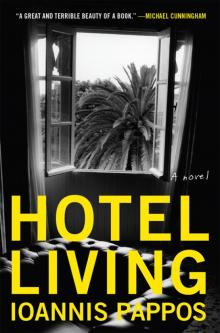

Hotel Living

Hotel Living Read online

CONTENTS

DEDICATION

PART I: ERIK

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

PART II: AFTER ERIK

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

CREDITS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

DEDICATION

To my three brothers, Savvas, Alek, and Christos

PART I

Erik

ONE

I LEFT MY FISHING VILLAGE IN Greece because I was good at backgammon and ridiculously lucky. I was thirteen when a tourist saw me beating everyone in the village square and registered me for an aptitude test at a school in Athens. My mother cried when I left Trikeri. My father was out fishing, said he couldn’t take the day off, but he wasn’t the type for good-byes anyway. Ten years and two scholarships later, I graduated from the physics department of Stanford and got a programming job in Silicon Valley.

After rural Greek tempers and Stanford egos, engineers from India were damn fine people to work with. They were fantastically intelligent, possessed a discreet charm, and didn’t question authority. They worked as if they reported to someone higher. Married with mortgages, they exemplified the Bay Area’s civic, complacent order. They lived as if they would never leave.

I, however, did not. I was still curious; Northern California was not a destination. With the dot-com meltdown, my Silicon Valley enthusiasm fizzled out. I was getting more and more unsatisfied.

WHEN I TOLD MY COLLEAGUES that I was about to start an MBA in France, they were amused.

“Stathis, I didn’t know you spoke French!”

“France has business schools?” a Java programmer said, snorting a laugh.

“The Greek will take a wine course!”

But I was excited. Late that summer of 2002, I caught myself with a permanent smile at work. I drove around the Bay Area, windows down, nasty rap rock from that summer’s blockbuster sound track blasting from the stereo’s speakers. I would miss my exit and keep going down the highway, to Half Moon Bay, to ride a wave or two.

At my farewell lunch in Redwood City at a fancy Chinese restaurant, my colleagues grinned and wobbled. Someone squeezed my shoulder. Sure, it was my day, but after two rounds of layoffs—the payback from the tech bubble—everyone was cheering a legit departure. I leaned back in my chair and looked around the table. We all had something in common: we were educated immigrants who’d lacked opportunities back home. Some of us had had rough childhoods.

At first, an MBA was my plan B—insurance in case I wasn’t caught up in something bigger, like a business-technology job in Europe. But a couple of months into my applications, some MBA virus infected me. Brochures assured “the amalgamation of strategy, finance, and organizational behavior” (whatever that meant), but all I read was an understory, some buzz about “being there.” My interviews with alumni revealed a sky’s-the-limit optimism that took success for granted:

“. . . become an unscripted leader . . .”

“. . . the helicopter view of the corporate world . . .”

“. . . bonus culture, which is not about the money!”

“EBS is the best business school in the world. EBS is the business school of the world,” a McKinsey executive and European Business School graduate told me at the end of my interview. “You’ll be at the right place at the right time,” he said as I entered the elevator.

They got me.

I gave away my IKEA furniture, sold my Honda Civic to my boss’s daughter, and bought a one-way ticket to Paris. I boarded the plane, beaming. Once again, I was eager, Greek.

THE FIRST THING I NOTICED on campus was that everyone in my class had been around. Everyone spoke at least three languages—one of the school’s requirements—while via was the way to answer the “Where are you from?” question. Italians came “via the States and South America.” Brits came from “Cambridge via McKinsey.” People rarely asked where you grew up; it was where you’d worked and studied that mattered.

“From Greece, via Silicon Valley!” I’d say.

A forty-five-minute drive from Paris, the EBS campus was in the center of the Fontainebleau Forest next to a fifteenth-century palace. Most of the students lived in nearby châteaus maintained, barely, by once-wealthy, now in-decline counts who lived in the garden houses on their properties and collected rent from us who stayed in their crumbling grand courts.

I traded my one-bedroom apartment in a cookie-cutter San Mateo complex for the Château de Montmelian, a disintegrating four-hundred-year old mansion with Münchausen-esque roofs with gables and chimneys, all of it piled on thirty acres of thickly wooded land hiding abandoned nurseries, tennis courts, statues, and peacocks. Once unpacked, I realized I had stepped onto an Italian movie set, a stage for diversions—not in the least conducive to homework—while my class smelled of testosterone.

“MANAGEMENT CONSULTING IS RIDICULOUSLY OVERRATED,” said my classmate Paul, the balding son of a European prime minister, at a recruiting event that fall. He handed me a brochure for a consulting firm called Command.

I browsed the glossy leaflet. “You don’t care for ‘value innovation’? You don’t want to be a ‘game changer’?” I smiled, mocking the brochure, but Paul was distracted.

“Value my ass,” he mumbled. “Want to change the game? Go into private equity.”

“Yeah, hmm, I skipped school the day they handed out job offers,” I joked, but Paul was gazing around. He had brokered a fourthhand Renault for me that had belonged to a friend of his, a recent graduate, and I was getting uncomfortable about driving a car I still had not paid for—Paul was always “too busy” to pass me the money-wiring instructions.

“Yes. Next week. Promise. I promise,” Paul said when I mentioned something about writing him a check. He finally looked back at me. “This week is insanely busy. My mother is visiting. Which reminds me . . .” He paused and gave me a head-to-shoes look. “Stathis! You are Greek, fine. But this is a recruiting event, and you are wearing brown shoes.”

I gave my Filene’s Basement loafers a quick look. I used to wear sneakers to work on Fridays. “Uh, right,” I mumbled.

“In London you can get fired for that.”

“That’d first require having a job,” I whispered, wondering what exactly it would take for me to make a go of it here: studying? Shopping? Sucking up to schoolmates’ parents?

Paul placed his fist against my torso. “Just tell them your GPA, mate.”

I laughed. “Gotta split. I need to pack. Alkis and I are moving tomorrow.”

“Excuse me?”

“Montmelian got flooded.”

“You are joking!” Paul’s mouth stayed open. “The comte has totally dropped the ball. Really. Okay, let’s have a moving party.”

“Paul!”

“A moving lunch. Beer and takeout, simple. I’ll bring the gang.” Paul was excited. My loss was his excuse to get wasted.

“Great,” I said flatly.

He gave me an apologetic look, as if to say: This is a small price to pay to be one of us, Greek boy.

THE NEXT DAY I MOVED with Alkis, my London Greek via

Harvard, president of the student body, “château-mate,” from Montmelian’s main court to a freezing shed at the edge of the property. The entire shack was a thirty-by-thirty box split into three murky bedrooms and a mice-infested kitchen.

A crowd showed up, indeed, which turned the hut’s extra bedroom into a falafel-and-cigarette-smelling living room. Slouched on a bed, Paul held court, describing our costumes for that evening’s party. Halfway through Alkis’s outfit he paused and picked up my hummus-crusted Valuation book, slowly, using only two fingers. “You might want to split these pages up before you get finger frostbite in this cabin,” Paul said, and threw my finance book at a dusty nightstand.

Sitting on the bed opposite him, I looked at the crusted hummus on my book and realized how ridiculously cold it was to sleep through the night.

“Mr. President!” I shouted to Alkis in the kitchen. “How’s fixing that heater coming along?”

But there was no reply.

Paul went on rolling a joint while planning his fiancée’s visit from London. In the thick of his third campus fling, he was rehearsing his plea. He looked at me: “Sleeping pills take away REM. We know that,” Paul said.

I just shrugged.

“When they didn’t let rats have REM sleep, you know what they did?” Paul asked, but no one spoke. “They went into sex overdrive. A frenzy. They couldn’t process it.”

I heard Alkis laugh in the kitchen.

“We know that rats have, what?” Paul continued, passing me the joint. “Two, three percent DNA difference from us?” He couldn’t be high yet; he had just lit the damn thing. “Stathis, you know what I’m talking about.”

I was about to burst out silly, but then I thought about how sometimes first class had few dealings with the real world. Extreme privilege could be surreal, but could also trigger funny social changes too. I took a hit and made an eyes-wide-open Paul-in-Wonderland yet brotherly face. “Malaka, listen,” I said, but tools banged and dropped in the kitchen.

“Cunting bugger!” Alkis yelled.

“Malaka!”

“Bastardo!”

“Cazzo!” Curses to the Montemelian comte all around.

I got up and made it into the kitchen, to find Alkis still in the loosened black tie he had worn on his way back from London that morning. He was yelling into his cell phone. “Yes!” Alkis shouted. “I’m looking for a plan B for sleeping tonight. Our heater’s a fucking recycling bin. Got a problem with that, mate?” He hung up. “Fat fuck!”

“Is this your moving tux?” I raised my eyebrows.

“Piss off, mate,” Alkis said. “I had to red-eye Eurostar. And it’s too bleeding freezing in this shithole to change.”

“How can one red-eye Eurostar?” I asked.

Alkis thought for a moment. “Mate, thanks for packing my crap last night. You’re my ace.”

“Don’t mention it,” I slurred. “Listen, an American who studies journalism at Oxford is coming to EBS for a couple of days. He’s writing an article on European business schools for his school paper in England. I think.”

“And?” Alkis said, browsing through contacts on his cell.

“The Dubyas thought it would make a good impression if he stayed at Montmelian.”

“Here?” He looked at me, annoyed. “Are they high?”

“LBS booked him at a Radisson, so we’re trying to be different. It’s only for a couple of nights,” I said.

“Fine. And if we don’t like his draft, we lock him indoors to die,” Alkis grumbled. Then, on his cell phone: “Hey, it’s me . . . your president?”

“I’ll tell him to crash in our study-living room thing,” I said, and turned to leave.

“Hold on, babe!” Alkis yelled into his phone, or to me. “Give the Dubya my room. I’m heading to Zurich on Sunday for job interviews. I’m not back until the middle of next week.”

“Good,” I said. “Gotta run.”

Alkis looked at me suspiciously.

“I need to stop by the prof courts before training,” I said.

“Hobnobbing with the faculty now, are we?”

My eyes drifted. Truth was, I felt at home around professors. There was something in them that I could not see in Paul, and even in Alkis. The faculty must already have grappled with career anxieties, and many of them, like me, had left their homelands to get ahead and make some money. “It’s just rugby.” I tried to dismiss Alkis. “Carpooling for training with—”

“Corporate Finance rugbies?” he laughed. “The twat’s forty.”

I was getting ready to counter him, but Alkis was back on his phone: “No, no. Not at all, baby. Of course not. Of course I’ll be at your dinner.” He put his thumb over the speaker of his cell phone. “When’s the Al Jazeera dinner?” he distress-whispered to me.

“Whenever you want!” Paul said, marching into the kitchen in the black paramilitary hood—Ustaše badge pinned on—that he planned to wear at that evening’s annual EBS S&M party at the largest château in the forest. He checked his reflection in the kitchen window, fixed the hood, and pulled a travel guidebook from his back pocket. I pretended not to notice him, but he began to read aloud:

“There is an end-of-the-world feel about this part of Pelio, as the road to Trikeri becomes more and more desolate. If you like taking one step farther even than those who have gotten away from it all, head for this little island with a year-round population of less than 150, just off the coast of the Pagasitikos Gulf. But the main pastime in Trikeri is explaining to locals why you’re there—and then explaining to yourself why you’re leaving.”

Paul lifted his hood. “So, why did you leave?”

“’Cause I didn’t wanna fish no more,” I said calmly but shortly. “And I believe you read the word desolate.” I exhaled and stood still. I hadn’t been back home for a while, to avoid mandatory service in the Greek army, something that made me self-conscious even in front of half-Greeks like Alkis. I looked around. Paul was playing with the shoe box by the sink that served as our mousetrap, and Alkis was listening to voice mails.

“Cunt,” Alkis said, and pressed 7 to delete the message.

“OUR CRUSH ON MANAGEMENT CONSULTING jobs comes from the Europeans’ silliness,” Paul told me at the campus bar after my training.

We were both sweaty, me from rugby, Paul from running around finishing nothing—from being Paul. I dried my face with the towel over my shoulders, but sweat kept dripping onto the bar.

“Silliness?” I asked.

“Europeans have this chip about money. We think that we’re above it,” Paul said, and downed his beer. “We act as if banking is not intellectually challenging enough. Like it’s only good for Americans and emerging markets.”

“What about entrepreneurship?”

He narrowed his eyes. “That’s okay. For the Brits.”

“I respect money,” I said.

“Stathis, you respect money ’cause you don’t have any. You grew up in a fishing village in Greece. Look around. People didn’t come here to have a career or become rich. This is not Wharton. You get to play with classmates who happen to be royals. With me! You learn how to manage down schoolmates from Japan and India, and how to dress up for balls and Michelin-starred restaurants in Barbizon. You’re in a Fitzgerald camp for children.” He pulled the towel from my shoulders and dried off his face and neck.

“Sounds exhausting,” I said, glancing around awkwardly. The campus bar was getting busy. A guy from my finance group was staring at us. I wasn’t sure how to deal with the bar, with EBS—with anything. Paul was deconstructing a world that I was trying to enter just by being there. I was probably a joke for him. Amusing. There could never be a real friendship between us. “I thought they taught us that managing and leading are different,” I half joked.

He tossed the towel back at me. “You’re full of shit—that’s why y

ou are here.”

I took issue. Pollyanna or not, I’d left my village with some sense of responsibility. I’d taken out student loans for EBS, which meant that skills and career goals were vested there, and since its academic intensity was considered one of the highest in the world, I took EBS seriously.

Yet, proving Paul’s point, half my class already had jobs lined up, which allowed for a campus hedonism of epidemic proportions: a final year of partying, of “don’t-ask-but-please-do-tell” promiscuity mixed with sleeping pills, pills, driving drunk in the forest, and any other type of self-indulgence as long as you stayed cocky or “MBA-bohemian” about it. Each week was dedicated to a country, whose students hosted alcohol-soaked blowouts that built up to weekend wickedness. On top of that, there were “party playoffs”: the Summer Ball, hosted either at the Château de Courances or at Versailles; the Winter Ball; the Montmelian Ball—all black tie—the Bois le Roi parties; the Farmers’ party (planned around a cave); the “Crossover” party—for crossing the middle of the academic year—where guys wore girls’ clothes and vice versa; and, of course, that evening’s S&M party in the chambers of the Château de Fleury-en-Bière, an EBS tradition that sent students all the way to Pigalle sex shops to get outfits, and summed up all my campus disillusionments about Paul’s play-for-future-network mantra. He was selling me indulgence as the first step toward old-world entitlement; a puzzling concept, but after three years of programming C++—and another ten of studying, working, and constantly proving myself—I didn’t mind a sample. I mean, come on, I was in a French forest. I could play for a change. For a bit.

I finished my pint and hit the bar with my glass. “Are you bringing your fiancée to the S&M tonight?” I asked, trying to find out how deep his dirt went.

“That’s where we met two years ago.” Paul smiled teasingly. “So, what do you think?”

My curiosity had put me on the spot. “You said you wanted to work on your engagement,” I said carefully. “So, I guess not?”

Paul gave my empty glass a once-over, almost reached for it, gave me a brother-handshake instead. I mirrored him tentatively, awkwardly—hand, arm, and shoulder, then hand again—guessing that I was being rewarded for my answer. He slowly stretched and disengaged our sweaty fingers. “Try again,” Paul said. Once more, I looked around.

Hotel Living

Hotel Living